Dave Usher was a truly great photographer. He primarily used large format cameras to create images of the natural scene that exhibited great beauty and sensitivity. He passed away last September. Dave was a photographer whose work deserved to be more widely known. He touched many lives but I’ll bet most who met him are not aware that he’s gone. Knowing Dave, he probably would not have wanted me to write this but I feel it’s important that I do. Not much he can do about it I guess.

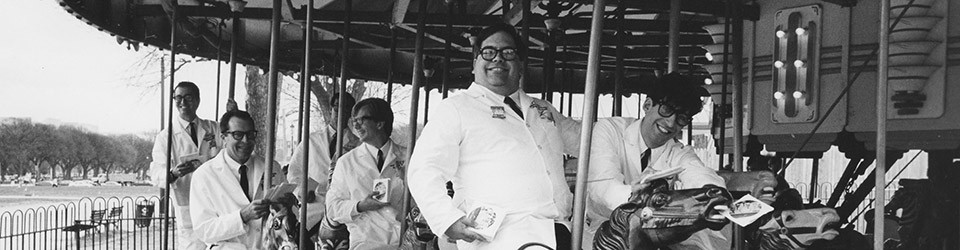

Dave was a former Army photographer and supervisory photographer for the US Department of Interior. Interior was his home but he made important photographs for many US government agencies including the State Department. Many know him for the twenty years he taught with Fred Picker at the famous Zone VI Workshops. Dave knew more about the history of photography, major photographers and photographic processes that anyone I had ever met. But most importantly he was a damned good photographer. His photographs are held in collections worldwide and appeared in major publications including National Geographic, The Washington Post and The New York Times. He was entrusted to print the glass plates of William Henry Jackson for the Smithsonian and for the show William Henry Jackson: The Survey Years.

Dave was a cantankerous son of gun who just happened to be a photographic master. Dave was also one of the most caring and unselfish people I ever met. He was also a friend, even though there occasional spats. We had a sometimes-difficult relationship … and I now have learned that he is gone.

My first experience with Dave was when I gave him a phone call in the late Nineties. Turns out he lived about a mile from my house in Northern Virginia. I knew about Dave from my reading of Zone VI newsletters. Dave was one of Fred’s key instructors, so when I found out he lived nearby it only made sense for me to contact him out of the blue and suggest he offer me a private workshop. True to form, I heard a growl and a got few choice words from the other end of the line that I won’t share here, and that was that.

A couple of years latter I decided to take a flyer and drive to Vermont to attend Fred’s funeral. I never met Fred, but had spoken to him several times by phone, owned a lot of his darkroom gear and chemicals, and of course was a devoted reader of his Newsletters. I heard about his death and a couple of days later hoped into my Miata and drove up to Dummerston. When I got there I didn’t know a soul, but had some new friends by the time I left. Everyone wondered who I was and why I was there, but Dave finally introduced himself, took me under his wing and introduced me to Zone VI brethren. I met some wonderful people, ended up sharing a few meals and made some photographs together.

Back in Virginia, Dave and I became good friends and we spent a lot of time together. One day he announced he was retiring from the government and would be moving to Brattleboro, Vermont to photograph full time. And so he did. I visited Dave several times to photograph, once with my son. We always had a great time together even though we didn’t always see eye to eye on things … politics, religion, and pretty much most other things … except our love of photography! In September 2014 Dave had a beautiful show of his work at the Vermont Center for Photography. I drove up to see it and stayed with him and Maria. His landscape work had a purity of vision that is seldom experienced.

Dave developed pancreatic cancer, a cruel card to be dealt. When he was feeling stronger I went to visit him and Maria. We ate a lot and photographed. Dave even showed me Fred’s secret“Point Lobos of the East”spot. We had a great time until we got into a stupid disagreement over something completely unimportant. There were no goodbyes the next morning when it was time for me to leave. I tried to reconnect shortly thereafter without success and chose to let it lie. Maybe it was the cancer, the chemo, or the radiation. I’ll never know. Maybe it was both of us. I never ended up telling Dave about what I was doing to make photography an even greater part in my life … not about this website, my exhibiting, my teaching or anything else.

It always bothered me. People who knew Dave told me that’s the way it was; time to move on. I should have done otherwise.

For the last month or so I have been thinking about Dave. While I was attending the Photo Arts Xchange I learned that Dave had passed away last September from the cancer. On the drive back home I called his friend, the photographer, camera builder and repairman extraordinaire Richard Ritter to see if there were any other details. True to form, Richard had spoken to Dave the day before he died and everything seemed fine. He only found out about Dave’s passing by accident when he ran into Maria several weeks later at the grocery store. I guess that’s the way Dave wanted it.

I should have been the bigger person and made a greater effort to reach out to Dave. I didn’t, and for that I will always feel terribly sad.

I hope this somehow reaches those who knew Dave … knew his larger than life personality, the tremendous good he did, the vast knowledge he shared and the timelessness of the work he created.

Dave, I will miss you.

Rest in peace big guy.