Awhile back I found an interview on the Internet (streetviewphotography.net) of social documentary and street photographer John Free. So important that I wrote about it before. But recently I have been thinking about it again. Probably because I have been going through proof sheets for the annual block of time I set aside for year-end printing, and because I recently had a few conversations about making more effective street photographs. What Free said was spot on and bears repeating again in this entry.

“My professional work in social documentary photography was very helpful in teaching myself how to get closer to the subject. Closer in many ways, not just where I stand, but how I can convey my feelings about a subject in my photograph of that subject. To bring as much life and understanding into the image, in order for the viewer to better understand the image.”

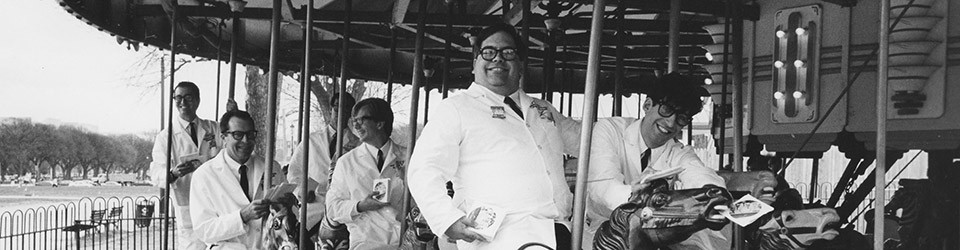

Free is a black and white film photographer and he expressed what I often feel when I am out there making photographs. I strongly believe that the black and white film experience enables a purity of vision, especially concerning social documentary and street work that other approaches simply cannot equal. But to make the image truly effective, to say what you want to say, you must get close to the subject. I tell this to my students and photographer friends that wish to listen. A few feet away, with a 35mm or 50mm lens. That’s it. Blend in with the surroundings, smile if that helps and make the exposure. If you’re nervous ask permission. Look at the work of the great’s … same approach (some like Garry Winogrand used a 28mm and got very close!).

In the end you have to do what works best for the images you are trying to make, but stop fooling yourself by thinking that your telephoto or bazooka zoom lens will be as effective as a simple camera armed with a shorter prime lens for extracting the essence of what you seek and wish to express.

Try it.