Another giant is gone. Not sure what I can add to what’s been said, so I’ll quote from The Guardian’s great piece describing the life and importance of this truly mythical and amazing photographer who passed away on May 23rd. Here is the link and an excerpt from the longer excellent tribute that appeared that same day.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/may/23/sebastiao-salgado-photographer-death-legacy

“It’s a testament to the epic career of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, who died this week at the age 81, that this year has already seen exhibitions of hundreds of his photos in Mexico City, France and southern California. Salgado, who in his lifetime produced more than 500,000 images while meticulously documenting every continent on Earth and many of the major geopolitical events since the second world war, will be remembered as one of the world’s most prodigious and relentlessly empathetic chroniclers of the human condition ….

Given everything that Salgado shot over his incredible six decades of work, it’s hard to imagine what else he could have done. Upon turning 80 last year, he had declared his decision to step back from photography in order to manage his enormous archive of images and administer worldwide exhibitions of his work. He also showed his dim outlook for humanity, telling the Guardian: “I am pessimistic about humankind, but optimistic about the planet. The planet will recover. It is becoming increasingly easier for the planet to eliminate us.”

It will probably take decades to fully appreciate and exhibit Salgado’s remaining photographs, to say nothing of grappling with the images he showed during his lifetime. One hopes that amid a period of increasing global strife, environmental collapse and threats to the mere notion of truth, this remarkable output will remain a beacon of decency and humanity – and help us chart a path back from the brink.”

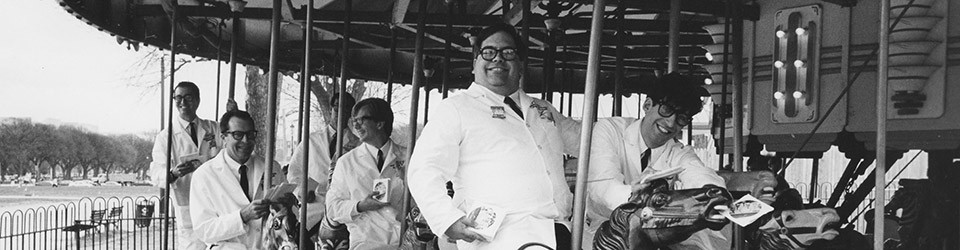

Strangely enough I don’t own any of Salgado’s monumental books coving the human condition and our planet. I’ve seen exhibits of his work, but for some reason never got around to including him in my library all these years. I’ve whiffed on a few of the great ones before and can’t explain why this glaring hole exists, but will now rectify the situation post haste! Don’t make the same mistake I’ve made. Get at least one of his epic books! Here’s a partial list for us to work from: Genesis; Amazonia; The End of Polio: A Global Effort to End a Disease; Sahel: The End of the Road; Kuwait: A Desert on Fire: Terra; Workers; and Migrations.

Stay well,

Michael